History of the Maldives

| History of the Maldives | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-dynastic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynastic ages | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Modern history | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

The history of the Maldives is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and surrounding areas in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is formed of 26 natural atolls, comprising 1,194 islands.

Historically, the Maldives has held strategic importance due to its location on the major marine routes of the Indian Ocean.[1] The Maldives' nearest neighbors are the British Indian Ocean Territory, Sri Lanka, and India.[2][3] The United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, and some Indian kingdoms have had cultural and economic ties with the Maldives for centuries.[1] In addition to these countries, Maldivians also traded with Aceh and many other kingdoms in what is now Indonesia and Malaysia. Specifically, the Maldives provided the primary source of cowrie shells, which were then used as currency throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast.[1]

Most likely, the Maldives were influenced by the Kalingas of ancient India. The Kalingas were the earliest region of India to trade with Sri Lanka and the Maldives; thus, they were responsible for the spread of Buddhism. Stashes of Chinese crockery found buried in various locations in the Maldives also show that there was direct or indirect trade contact between China and the Maldives. In 1411 and 1430, the Chinese admiral Zheng He (鄭和) visited the Maldives; the Chinese later became the first country to establish a diplomatic office in the Maldives when the Chinese nationalist government, based in Taipei, opened an embassy in Malé in 1966. The Embassy of the People's Republic of China has since replaced this office.

After the 16th century, when colonial powers took over much of the trade in the Indian Ocean, Maldivian politics were interfered with by the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and then the French.[4] However, this interference ended when the Maldives became a British Protectorate in the 19th century. Under this circumstance, the Maldivian monarchs were granted a measure of self-governance.

The Maldives gained total independence from the British on 26 July 1965.[5] However, the British continued to maintain an air base on the island of Gan in the southernmost atoll until 1976.[1] The British departure in 1976, at the height of the Cold War, almost immediately triggered foreign speculation about the future of the air base.[1] The Soviet Union requested the use of the base, but the Maldives refused.[1]

The republic's greatest challenge in the early 1990s was the need for rapid economic development and modernization given the country's limited resource base in fishing and tourism.[1] Concern was also evident over a projected long-term sea level rise which would prove disastrous to the Maldives' low-lying coral islands.[1]

Early Age

[edit]Much of the history of the Maldives is unknown. However, based on legend and actual data, it can be deduced that the islands have been inhabited for over 2,500 years according to an old folklore from the Maldives' southern atoll.

During Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar I's rule in the 17th century, Allama Shihabuddine, of Meedhoo on Addu Atoll, wrote the book Kitab Fi al-Athari Midu al-Qadimiyyah (On the Ancient Ruins of Meedhoo) in Arabic. The account is strikingly consistent with known South Asian history, referencing Emperor Asoka, the legendary Indian emperor.[6] It also backs up parts of the facts found in old Maldivian records and the Loamaafaanu copper plates. Legends from the past, inscriptions on the copper plates, ancient writings engraved on coral items, and stories repeated by the language and traditions of the people have also told of the Maldives' history.[6]

Compared to the southern islands, up to 800 kilometers away, the northern islands may have had a different migratory and colonization history.[7]

The first settlers to the southern Maldives

[edit]A delegation from the Divi people sent gifts to the Roman Emperor Julian according to a fourth-century note published by Ammianus Marcellinus in 362 AD (1937, Rolfe). ("Divi" is remarkably similar to "Dheyvi," and thus they may refer to the same people.)

The Redi and the Kunibee, from India's Mahrast area, were among the later settlers. The people from northern India arrived in the Maldives roughly during the sixth to fifth centuries B.C.—three centuries before Emperor Asoka built his state in India. According to folklore, they were not native to India and had arrived from another country. Hinduism was also brought to the Maldives during this period (Shihabuddine, c. 1650–1687).[6]

Dheeva Maari

[edit]The Dheyvis found Suvadinmathi (the Huvadhu Atoll) after their first settlement in Isdhuva in Isduvammathi (the Haddhunmathi Atoll) according to Shihabuddine.[6][8] These people gave the term "duva" to each island where they first lived and discovered.[8] They went on to establish the Kingdom of Dheeva Maari.[8]

The first known monarch of the Dheevis

[edit]The kingdom of Adeetta Vansa was formed in Dheeva Maari by Sri Soorudasaruna Adeettiya; he was the first known monarch of the Dheyvis of Dheeva Maari. He had been the exiled prince of Kalinga kingdom before he founded the kingdom of Adeetta Vansa, and this founding preceded the creation of the kingdom of Malik Aashooq.[8]

Once, a group from Bairat came to Dheeva Mahal to preach the beliefs and works of Buddha. (Dheeva Mahal was the name given to Dheeva Maari during the time.[8])

The first settlers to the northern Maldives

[edit]According to folklore, the northern atolls of Maldives were populated by other tribes from southern India with darker skin colors. According to legends, the islands they populated were named Nolhivaram, Kuruhinnavaram, and Giravaram (Shihabuddine, c. 1650–1687). These islands are now known as Nolhivaramu, Hinnavaru, and Giravaru. (The names likely evolved over many centuries to their current form.[6])

Comparative studies of Maldivian oral, linguistic, and cultural traditions and customs indicate that some of the earliest settlers to the northern Maldives were descendants of fishermen from the southwest coasts of present India and the northwestern shores of Sri Lanka. One such community is the Giraavaru people.[9] They are mentioned in ancient legends and local folklore, specifically in regards to the establishment and kingly rule of the capital, Malé.

Some argue, from the presence of Jat Gujjar titles and Gotra names, that the Sindhis also accounted for an early layer of migration. Seafaring from Debal began during the Indus Valley civilization, and the Jatakas and Puranas show abundant evidence of this maritime trade; the use of similar traditional boatbuilding techniques in Northwestern South Asia and the Maldives, as well as the presence of silver punch mark coins from both regions, gives additional weight to this. Additionally, shere are minor signs of Southeast Asian settlers, likely some adrift from the main group of Austronesian reed boat migrants that settled Madagascar.[10]

Kingdom of Adeetta Vansa

[edit]The Kingdom of Adeetta Vansa (Solar Dynasty), formed in Dheeva Maari, ruled until the establishment of the Kingdom of Soma Vansa (Lunar Dynasty). Soma Vansa was born in Kalinja; Adeetta Vansa was born in Kalinja as well.[clarification needed] The Kingdom of Soma Vansa was founded by the son of a Soma Vansa monarch who ruled in Kalinja at the time. (Sri Balaadeettiya was the first king of Soma Vansa, while Queen Damahaar, his wife, was the final queen of Adeetta Vansa. Therefore, while the dynasty's name was altered to Soma Vansa, the monarchs were still related to both Soma Vansa and Adeetta Vansa.) Dheeva Maari turned to Islam over a century and a half later.[8]

Kingdom of Soma Vansa

[edit]At the start of the Soma Vansa dynasty, the Indian ruler Raja Dada invaded Dheeva Maari's northern two atolls, Malikatholhu and Thiladunmathi, and took control of them. Sri Loakaabarana, Sri Maha Sandura, Sri Bovana Aananda, as well as his son and brother, were the most recent five monarchs of Soma Vansa before the advent of Islam. After Sri Maha Sandura passed away, Raja Dada ascended to the crown.[8]

Mahapansa

[edit]Sri Maha Sandura's daughter, Kamanhaar (sometimes spelled Kamanaar), and Rehendihaar were exiled to the island of Is Midu. With her, she took Maapanansa, a book that contained the history of Adeetta Vansa's kings. In his work, Al Muhaddith Hasan claims to have read the entire Maapanansa, which was written on copper. He also claims to have buried all of Maapanansa's parts. Sri Mahaabarana Adeettiya (Sri Bovana Aananda's son) ascended to the throne after him, after which he defeated the Indians who controlled Malikatholhu and Thiladunmathi. (The Indians belonged to the same tribe as Raja Dada, who was the first to conquer these two atolls.) Afterward, Sri Mahaabarana Adeettiya was given the title of monarch over 14 atolls and 2,000 islands. Malikaddu Dhemedhu, between Minicoy and Addu, became his Dheeva Mahal.[8]

Ancient names of atolls of Maldives according to Maapanansa

[edit]- Thiladunmathi[8]

- Miladunmaduva[8]

- Maalhosmaduva[8]

- Faadu Bur[8]

- Mahal Atholhu[8]

- Ari Adhe Atholhu[8]

- Felide Atholhu[8]

- Mulakatholhu[8]

- Nilande Atholhu[8]

- Kolhumaduva[8]

- Isaddunmathi[8]

- Suvadinmathi[8]

Archaeological remains of the first settlers

[edit]The first Maldivians haven't been known to leave any archaeological remains. It is speculated that their buildings were likely built of wood, palm fronds, and other perishable materials which would have quickly decayed in the salt and wind of the tropical climate. Moreover, chiefs or headmen didn't reside in elaborate stone palaces, nor did their religion require the construction of large temples or compounds.[11]

Earliest written history

[edit]The earliest written history of the Maldives is marked by the arrival of Sinhalese people. These people descended from the exiled Vanga Prince Vijaya from the ancient city known as Sinhapura in northeast India. He and his party of several hundred landed in Sri Lanka; some ended up in the Maldives circa 543–483 B.C. According to the Maapanansa, one of the ships that sailed with Prince Vijaya, who went to Sri Lanka around 500 B.C., went adrift and arrived at an island called Mahiladvipika, which has since been identified with the Maldives. It is also said that at that time, the people from Mahiladvipika used to travel to Sri Lanka.

The Sinhalese settlement in Sri Lanka and the Maldives marks a significant change in demographics and the development of the Indo-Aryan language Dhivehi, which is most similar in grammar, phonology, and structure to Sinhala and especially to the more ancient Elu Prakrit, with has less Pali influences. [citation needed]

Alternatively, it is believed that Vijaya and his clan came from western India. This claim has been supported by linguistic and cultural features, as well as specific descriptions in the epics themselves, e.g. the detail that Vijaya visited Bharukaccha (Bharuch in Gujarat) in his ship on a southward voyage.[10]

Philostorgius, a Greek historian of Late Antiquity, wrote of a hostage among the Romans who hailed from the island called Diva, which is presumed to be the Maldives; his name was Theophilus. Theophilus was sent around the year 350 to convert the Himyarites to Christianity and went to his homeland from Arabia; he returned to Arabia, visited Axum, and settled in Antioch.[12]

Caste system in Maldives

[edit]The Maldivian society serves as an example of a social structure which has shed a lot of stratification-related characteristics, though it still holds onto certain remnants of its former caste society.[13]

Buddhist period

[edit]

Despite being just mentioned briefly in most history books, the 1,400-year-long Buddhist period has foundational importance in the history of the Maldives. It was during this period that much of the culture of the Maldives developed and flourished. The Maldivian language, the first Maldive scripts, the architecture, the ruling institutions, and the customs and manners of the Maldivians originated from the time when the Maldives were a Buddhist kingdom.[14][page needed]

Before embracing Buddhism as their way of life, Maldivians had practiced an ancient form of Hinduism, specifically ritualistic traditions known as Śrauta in the form of venerating the Surya (the ancient ruling caste were of Aadheetta or Suryavanshi origins).[15]

Buddhism likely spread to the Maldives in the third century B.C., the time of Aśoka. Nearly all archaeological remains in the Maldives are from Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and all artifacts found to date display characteristic Buddhist iconography. Archeological evidence from an ancient Buddhist monastery in Kaashidhoo has been dated between 205 to 560 AD, based on the radiocarbon dating of shell deposits unearthed from the foundations of stupas and other structures in the monastery.[16]

Maldivian Buddhist (and Hindu) temples were mandala-shaped and oriented according to the four cardinal points, with the main gate being toward the east. The ancient Buddhist stupas are called "havitta," "hatteli," or "ustubu" by the Maldivians according to the different atolls; these stupas and other archaeological remains, like foundations of Vihāra, with compound walls and stone baths, are found on many islands of the Maldives. They usually lie buried under mounds of sand and are covered by vegetation. Local historian Hassan Ahmed Maniku counted as many as 59 islands with Buddhist archaeological sites in a provisional list he published in 1990. The largest monuments of the Buddhist era are in the islands fringing the eastern side of the Haddhunmathi Atoll.[citation needed]

In the early 11th century, the Minicoy and Thiladhunmathi, and possibly other northern Atolls, were conquered by the medieval Chola Tamil emperor Raja Raja Chola I, after which they became a part of the Chola Empire.[citation needed]

The unification of the archipelago is traditionally attributed to King Koimala. According to a legend from Maldivian folklore, in the early 12th century A.D., a medieval prince named Koimala, who was a nobleman of the Lion Race from Sri Lanka, sailed to Rasgetheemu island (literally "Town of the Royal House" or figuratively "King's Town") in the North Maalhosmadulu Atoll. From there, he sailed to Malé and established a kingdom named Dheeva Mari.[citation needed]

By then, the Aaditta (Sun Dynasty, from the Suryavanshi ruling caste) had ceased to rule in Malé, possibly because of invasions by the Cholas of Southern India in the 10th century. Koimala, who reigned as King Mahaabarana, was a king of the Homa (Lunar Dynasty, from the Chandravanshi ruling caste), which some historians call the House of Theemuge.[17] The Homa sovereigns intermarried with the Aaditta sovereigns. This is why the formal titles of Maldivian kings, until 1968, contained references to "kula sudha ira", meaning "descended from the Moon and the Sun". No official record exists of the Aaditta dynasty's reign.

Since Koimala's reign, the Maldives' throne was known as the Singaasana or Lion Throne.[17] Before then, and in some situations since, it was also known as the Saridhaaleys or Ivory Throne.[18] Some historians credit Koimala with freeing the Maldives from Chola rule.[citation needed]

Western interest in the archaeological remains of early cultures in the Maldives began with the work of H.C.P. Bell, a British commissioner of the Ceylon Civil Service.[1] Bell was first ordered to the islands in late 1879[19] and returned several times to the Maldives to investigate ancient ruins.[1] He studied the ancient mounds, called havitta or ustubu (names derived from chaitiya and stupa), which were found on many of the atolls. Notably, there's one Havitta on Fuvahmulah.

Early scholars—like Bell, who resided in Sri Lanka for most of his life—have claimed that Buddhism came to the Maldives from Sri Lanka and that the ancient Maldivians followed Theravada Buddhism. Since then, new archaeological discoveries point to Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist influences as well, which are likely to have come to the islands straight from the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed] An urn discovered in Maalhos (the Ari Atoll) in the 1980s had a Vishvavajra inscribed with Protobengali script. This text was in the same script used in the ancient Buddhist centers of learning in Nalanda and Vikramashila.

Later, in the mid-1980s, the Maldivian government allowed Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl to excavate ancient sites.[20] Heyerdahl studied the ancient mounds, or Havitta, found on many atolls.[20] Some of his archaeological discoveries of stone figures and carvings from pre-Islamic civilizations are today exhibited in a side room of the small National Museum.[20] Heyerdahl's research indicates that as early as 2,000 B.C., the Maldives were a part of the maritime trading routes of early Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Indus Valley civilizations.[20]

In the National Museum, there is also a small porites stupa; on it, the directional Dhyani Buddhas (Jinas) were etched in its four cardinal points in the Mahayana tradition. Some coral blocks with fearsome heads of guardians also displayed Vajrayana Iconography. Additionally, Buddhist remains have been found in Minicoy Island, once part of a Maldivian kingdom, by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in the latter half of the 20th century. Among these remains were a Buddha head and stone foundations of a Vihara.[citation needed]

Islamic period

[edit]Introduction of Islam

[edit]

The importance of the Arabs as traders in the Indian Ocean during the 12th century may partly explain why the last Buddhist king of Maldives, Dhovemi, converted to Islam in the year 1153[20] (or 1193, as certain copper plate grants give a later date[citation needed]). The king adopted the Muslim title and name of Sultan Muhammad al Adil, thus initiating a series of six dynasties consisting of 84 sultans and sultanas that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective.[20] The formal title of the Sultan up to 1965 was, Sultan of Land and Sea, Lord of the Twelve-Thousand Islands, and Sultan of the Maldives, which came with the address of highness.[citation needed]

The person traditionally deemed responsible for this religious conversion in the Maldives was a Sunni Muslim visitor named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.[20] His venerated tomb now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy, across the street from the Hukuru Mosque in the capital Malé.[citation needed] Built in 1656, this remains the oldest mosque in Malé.[20]

In the history books used by Maldivians, the introduction of Islam at the end of the 12th century is considered the cornerstone of the country's history. The time before Islam is designated the time of Jahiliyyah, or ignorance.

Compared to other areas of South Asia, the conversion of the Maldives to Islam happened relatively late. Arab Traders had converted populations in the Malabar Coast since the seventh century, and the Arab conqueror Muhammad Bin Qāsim had converted large swathes of Sindh to Islam at around the same time. Meanwhile, the Maldives remained a Buddhist kingdom for another five hundred years, perhaps the southwest most Buddhist country, until its eventual conversion to Islam.

Certain artifacts, known as Dhanbidhū Lōmāfānu, give information about the suppression of Buddhism in the southern Haddhunmathi Atoll, previously a major center of that religion. Monks were taken to Malé and beheaded, and the Satihirutalu (the Chatravali crowning a stupa) were broken to disfigure the numerous stupas; additionally, the statues of Vairocana, the transcendent Buddha of the middle world region, were destroyed. [citation needed]

Arab interest in Maldives was also reflected in Ibn Battutah's residence there in the 1340s.[21] A well-known North African traveler, he wrote how a Moroccan, Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari, was believed to have been responsible for spreading Islam in the islands, reportedly convincing the local king after having subdued Ranna Maari, a demon coming from the sea.[22] Even though this report has been contested in later sources, some find that it does explain some crucial aspects of Maldivian culture. For instance, Arabic has historically been the prime language of administration in the Maldives rather than the Persian and Urdu languages used in the nearby Muslim states. Another link to North Africa is possibly the Maliki school of jurisprudence, used throughout most of North Africa, which was the official one of the Maldives until the 17th century.[23]

Berber Muslim Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari is traditionally credited for the Maldives' Islamic conversion. According to a story told to Ibn Battutah, a mosque was built with the inscription: "The Sultan Ahmad Shanurazah accepted Islam at the hand of Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari."[24][23] Some scholars also have suggested the possibility of Ibn Battuta misreading Maldivian texts and having a bias towards the North African, Maghrebi narrative of this Shaykh, instead of the East African or Persian origins account that was also well known at the time.[25]

Scholars have posited another scenario where Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari might have been a native of Barbera, a significant trading port on the northwestern coast of Somalia.[26] This is evidenced by, during his visit to Mogadishu, Ibn Batuta's mentioning that the Sultan at that time, Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh Omar, was a Berber. Ibn Batuta also stated the Maldivian king was converted by Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.[27]

Another interpretation, held by more reliable local historical chronicles, Raadavalhi and Taarikh,[28][29] is that Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari was Abdul Barakat Yusuf Shams ud-Dīn at-Tabrīzī, also locally known as Tabrīzugefānu.[30] In the Arabic script, the words al-Barbari and al-Tabrizi are very much alike, since at the time, Arabic had several consonants that looked identical and could only be differentiated by overall context. (This has since changed by addition of dots above or below letters to clarify pronunciation. For example, the letter "B" in modern Arabic has a dot below, whereas the letter "T" looks identical except there are two dots above it.) In sum, "ٮوسڡ الٮٮرٮرى" could be read as "Yusuf at-Tabrizi" or "Yusuf al-Barbari."[31]

Cowrie shells and coir trade

[edit]

Inhabitants of the Middle East became interested in the Maldives due to its strategic location. Middle Eastern seafarers had just begun to take over the Indian Ocean trade routes in the 10th century and found the Maldives to be an important link to those routes.[20] Specifically, the Maldives was the first landfall for traders from Basra sailing to Sri Lanka or Southeast Asia.[citation needed] Bengal was one of the principal trading partners of the Maldives.[citation needed] Trade between these regions involved mainly cowrie shells and coir fiber.[citation needed]

The Maldives had an abundant supply of cowry shells, a form of currency that was widely used throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast.[20] Shell currency imported from the Maldives was used as legal tender in the Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Bengal alongside gold and silver. In exchange for cowry shells, the Maldives received rice; the Bengal-Maldives cowry shell trade was the largest shell currency trade network in history.[32] The local name for cowry shells is Boli. There are several hundreds of these shells found on the beaches of the islands even today.

The other essential product of the Maldives was coir, the fiber of the dried coconut husk. Cured in pits, beaten, spun, and then twisted into cordage and ropes, coir's salient quality is its resistance to saltwater. It was used to stitch together and rig the dhows that plied the Indian Ocean. Maldivian coir was exported to Sindh, China, Yemen, and the Persian Gulf. "It is stronger than hemp," wrote Ibn Battuta, "and is used to sew together the planks of Sindhi and Yemeni dhows, for this sea abounds in reefs, and if the planks were fastened with iron nails, they would break into pieces when the vessel hit a rock. The coir gives the boat greater elasticity, so that it doesn't break up."

Colonial period

[edit]

Portuguese colonization and local revolt

[edit]In 1558, the Portuguese established a colony in the Maldives, which they administered from their main colony in Goa. This colony included the west coast of modern-day Kerala, Karnataka, and Ceylon. The Portuguese tried to impose Christianity on the locals; one native ruler converted to Christianity during this period and married D. Francisca de Vasconcelos, an órfãs do rei.[33]

In 1573, a local leader named Muhammad Thakurufaanu-al-A'uzam and his two brothers, Ali and Hassan, from Utheemu of North Thiladhumathi Atoll, organized a popular revolt to drive out the Portuguese from the islands.[34] The three brothers landed on a different island every night; they would fight the Portuguese and return to Utheemu before daybreak. On the first day of Rabi' al-Awwal, the brothers reached Malé. It had been rumored that the Portuguese garrison of Andreas Andre (locally known as Andhiri Andhirin, meaning "dark dark" or, in English, "Andrew Andrew")[35] had planned to come to the island and forcibly convert the local Maldivians into Christianity the night after. Knowing this, the local fighters were ready to die for their faith and people, to liberate their people from the outsiders. According to reports, Andreas Andre was killed by a musket shot by Muhammad Thakurufaanu himself. This eventually resulted in the surrender of the Portuguese troops, who thus left the islands. Afterwards, the local islanders chose Muhammad Thakurufaanu to be their sultan in 1573, thus putting the Utheemu dynasty in power until 1697.[36]

Every first day of Rabi' al-Awwal, the Maldives observes the Gaumee Dhuvas, or Maldives National Day, in remembrance of Muhammad Thakurufaanu. His home in Utheemu is known locally as Utheemu Ganduvaru or Utheemu Palace. Many pieces of furniture that were inside the house are now located inside the Maldives National Museum in Malé. A memorial center is also located near Utheemu Ganduvaru.

Dutch hegemony

[edit]In the mid-17th century, the Dutch came to take over the Maldives, and in the late 1650s (around 1658), the Dutch colonized the islands. They administered their colony in Ceylon, which in turn was administered by the Dutch East India Company. They then established hegemony over Maldivian affairs without directly involving themselves in local matters, which remained governed according to centuries-old Islamic customs.

In 1796, the local revolt disrupted the colonists; with British interference and pressure, the Dutch stepped down from the islands.

-

Map from the 1662 Tabula Indiae orientalis by Frederik de Wit

-

18th-century map by Pierre Mortier of the Netherlands depicting, with detail, the islands of the Maldives

-

1753 Van Keulen map of Ari Atoll

-

1753 Van Keulen map of Huvadu Atoll (inaccurate)

British protectorate

[edit]

The British expelled the Dutch from Ceylon in 1796, after which they Maldives as a British-protected area.[37] Britain had gotten involved with the Maldives as a result of domestic disturbances which targeted the settler community of Bora merchants, who were British subjects in the 1860s.[38] The rivalry between two dominant families, the Athireege clan and the Kakaage clan, was resolved with the former winning the favor of the British authorities in Ceylon.[39] The status of Maldives as a British protectorate was officially recorded in an 1887 agreement.[37]

On 16 December 1887, the Sultan of the Maldives Muhammad Mueenuddeen II signed a contract with the British Governor of Ceylon, turning the Maldives into a British-protected state and thus giving up the islands' sovereignty in matters of foreign policy but retaining internal self-government. The British government promised military protection and non-interference in local administration, which continued to be regulated by Muslim traditional institutions, in exchange for an annual tribute. The status of the islands thus was akin to other British protectorates in the Indian Ocean region, i.e.Zanzibar and the Trucial States.[citation needed]

During the British era, which lasted until 1965, the Maldives continued to be ruled by a succession of sultans.[37] It was a period during which the Sultan's authority and powers were increasingly and decisively taken over by the Chief Minister, much to the chagrin of the British Governor-General, who continued to deal with the ineffectual Sultan. Consequently, Britain encouraged the development of a constitutional monarchy, and thus the Maldives' first Constitution was proclaimed in 1932. However, the new arrangements favored neither the Sultan nor the Chief Minister but rather a young crop of British-educated reformists. As a result, angry mobs were instigated against the Constitution, which was publicly torn up.

The Maldives were only marginally affected by the Second World War. The Italian auxiliary cruiser Ramb I was sunk off Addu Atoll in 1941. In March 1944, the German submarine U-183 fired through the Gan channel, torpedoing the oil tanker British Loyalty that had been anchored in the Addu lagoon. The tanker was damaged but not sunk, and its oil spilt out into the lagoon and beaches. Over time, the British Loyalty was repaired and remained in the atoll for storage through the rest of the war. It was finally scuttled in January 1946 inside the atoll southeast of Hithadhoo.[40]

After the death of Sultan Majeed Didi and his son, the members of the parliament elected Mohamed Amin Didi as the next person in line to succeed him as Sultan.[41] However, Didi refused to take up the throne.[41] Afterwards, a referendum was held in 1952, and the Maldives became a republic with Amin Didi as the first elected president, marking the abolition of the 812-year-old sultanate.[citation needed]

While serving as prime minister during the 1940s, Didi nationalized the fish export industry.[37] He has also been remembered as a reformer of the education system and a promoter of women's rights.[37] However, while he was in Ceylon for medical treatment, a revolution was instigated by the people of Malé, headed by his deputy Velaanaagey Ibraahim Didi.[42] When Amin Didi returned, he was confined to Dhoonidhoo Island.[42] He escaped to Malé and tried to take control of Bandeyrige but was beaten by an angry mob. He died soon after.[43][44]

After the fall of Didi, a referendum was held in 1953. Ultimately, 98% of the people voted in favor of restoration of the monarchy,[45] so the country was once again declared a Sultanate. A new parliament was elected, as the former had been dissolved after the end of the revolution. The new parliament members decided to take a secret vote to elect a sultan, after which Prince Muhammad Fareed Didi was elected as the 84th Sultan in 1954. His first Prime Minister was Ibraahim Ali Didi, later known as Ibraahim Faamuladheyri Kilegefaan. On 11 December 1957, the Prime Minister was forced to resign, and Velaanagey Ibrahim Nasir was elected in his place the following day.

-

Illustration by CW Rosett in The Graphic depicting the royal palace

-

A hut of Tottiyan from Male island (illustration by Edgar Thurston, 1909)

-

Muhammad Amin Didi, President of the First Maldivian Republic (1953)

British military presence and Suvadive secession

[edit]

Beginning in the 1950s, political history in Maldives was largely influenced by the British military presence in the islands.[37] In 1954, the restoration of the sultanate still perpetuated the rule of the past.[46] Two years later, however, the United Kingdom obtained permission to reestablish its wartime RAF Gan airfield in Addu Atoll.[46] The Maldives then granted the British a 100-year lease on Gan that required them to pay £2,000 a year and around 440,000 square meters on Hitaddu for radio installations.[46] This served as a staging post for British military flights to the east and Australia, replacing RAF Mauripur in Pakistan (which had been relinquished in 1956).[47]

In 1957, Nasir called for a review of the agreement in the interest of shortening the lease and increasing the annual payment.[46] He also announced a new tax on boats.[citation needed] However, Nasir was challenged in 1959 by a local secessionist movement in the southern atolls which benefited economically from the British presence on Gan.[46] This group cut ties with the Maldives government and formed an independent state, the United Suvadive Republic, with Abdullah Afeef as president.[46] The short-lived state (1959–63) had a combined population of 20,000 inhabitants scattered over Huvadu, Addu and Fua Mulaku.[46]

Afeef pleaded for support and recognition from Britain in the 25 May 1959 edition of The Times of London.[48] However, the initial lukewarm support from the British for the small breakaway nation was withdrawn in 1961 when the British signed a treaty with the Maldive Islands without involving Afeef.[citation needed] Following that treaty, the Suvadives had to endure an economic embargo.[citation needed] Furthermore, in 1962, Nasir sent gunboats from Malé, with government police on board, in order to eliminate elements opposed to his rule.[46] One year later, the United Suvadive Republic was scrapped,[citation needed] and Abdullah Afif went into exile to the Seychelles[46] where he later died in 1993.[49]

Meanwhile, in 1960, the Maldives had allowed the United Kingdom to continue to use both the Gan and the Hitaddu facilities for a 30-year period with a payment of £750,000 over the period of 1960–1965 for the purpose of Maldives' economic development.[46] The base was eventually closed in 1976 as part of the larger British withdrawal of permanently stationed forces, "East of Suez," initiated by Harold Wilson's government.[50]

-

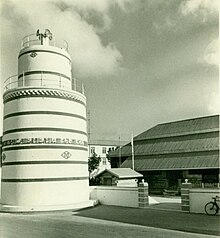

RAF camp on Addu Atoll established in 1944 as a base for flying boats operating in the Indian Ocean

-

RAF Short Sunderland moored in the lagoon at Addu Atoll during World War II

-

A wind break constructed from ration boxes protecting the small RAF camp at Kelai, Maldive Islands, which served as a refueling base for flying boats operating in the Indian Ocean

-

Abdullah Afif, leader of the secessionist United Suvadive Republic (1959–1963)

-

Coat of arms of the secessionist United Suvadive Republic

Independence

[edit]On 26 July 1965, Maldives gained independence under an agreement signed with United Kingdom.[46] However, the British government retained the use of the Gan and Hithadhoo facilities.[46] Later, in a national referendum in March 1968, Maldivians abolished the sultanate and established a republic.[46]

In line with the broader British policy of decolonization on 26 July 1965, an agreement was signed on behalf of His Majesty the Sultan by Ibrahim Nasir Rannabandeyri Kilegefan, Prime Minister, and on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen by Sir Michael Walker, British ambassador designate to the Maldive Islands. This ended the British responsibility for the "Defence and External Affairs" of the Maldives. The islands thus achieved full political independence, with the ceremony taking place at the British High Commissioner's Residence in Colombo. After this, the sultanate continued for another three years under Muhammad Fareed Didi, who declared himself King rather than Sultan.

On 15 November 1967, a vote was taken in parliament to decide whether the Maldives should continue as a constitutional monarchy or become a republic. Of the 44 members of parliament, 40 voted in favor of a republic. On 15 March 1968, a national referendum was held on the question, and 81.23% of those taking part voted in favor of establishing a republic.[51] The republic was declared on 11 November 1968, thus ending the 853-year-old monarchy. Ibrahim Nasir, the former prime minister, became the republic's first president. Under the new constitution, Nasir was elected indirectly to a four-year presidential term by the Majlis (legislature)[46] and his candidacy later ratified by referendum.[citation needed] He appointed Ahmed Zaki as the new prime minister.[46] As the Maldives' king had held little real power before, this was seen as a cosmetic change and required few alterations in the structures of government.

Nasir Presidency

[edit]In 1973, Nasir was elected to a second term under the constitution as amended in 1972, which extended the presidential term to five years and also provided for the election of the prime minister by the parliament.[46] In March 1975, Zaki was arrested in a bloodless coup and was banished to a remote atoll.[46] Observers suggested that Zaki had been becoming too popular and hence posed a threat to the Nasir faction.[52]

Nasir is widely credited with modernizing the long-isolated and nearly unknown Maldives and opening them up to the rest of the world, including by building its first international airport (Malé International Airport) in 1966 and bringing the Maldives to United Nations membership. He also laid the foundations of the nation by modernizing the fisheries industry with mechanized vessels and starting the tourism industry—the two prime drivers of today's Maldivian economy. Tourism in the Maldives developed further through the 1970s; the first resort was Kurumba Maldives which welcomed its first guests on 3 October 1972.[53]

Nasir was additionally credited with many other improvements such as introducing an English-based modern curriculum to government-run schools and granting Maldivian women the right to vote in 1964. He also brought television and radio to the country with formation of Television Maldives and Radio Maldives for broadcasting radio signals nationwide. Furthermore, he abolished Vaaru, a tax on the people living on islands outside Malé. The first accurate census was held in December 1977 and showed 142,832 persons residing in Maldives.[54]

However, during the 1970s, the economic situation in Maldives suffered a setback when the Sri Lankan market for Maldives' main export of dried fish collapsed.[55] Additionally, the British closed its airfield on Gan in 1975.[55] A steep commercial decline followed its evacuation.[55] As a result, the popularity of Nasir's government suffered.[55] Furthermore, Nasir was generally criticized for his authoritarian methods against opponents, as well as for his iron-fisted methods in handling an insurrection by the Addu islanders who formed a short-lived breakaway government, the United Suvadives Republic, with closer ties to the British.[56] Additionally, Nasir's hasty introduction of the Latin alphabet (Malé Latin) in 1976, instead of the local Thaana script, which was reportedly done to promote the use of telex machines in the local administration, was widely criticized. Clarence Maloney, a Maldives-based U.S. anthropologist, lamented the inconsistencies of the "Dhivehi Latin" which ignored all previous linguistic research on the Maldivian language and didn't follow the modern Standard Indic transliteration.[57] At the time of romanization, every island's officials were required to use only one script, making them illiterate overnight. (Officials were relieved when the Tāna script was reinstated by President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom shortly after he took power in 1978. However, Malé Latin continues to be widely used.)

Maldives's 20-year period of authoritarian rule under Nasir ended in 1978 when he fled to Singapore.[55] A subsequent investigation revealed that he had absconded with millions of dollars from the state treasury.[55] When Nasir relinquished power, Maldives was debt-free and the national shipping line with more than 40 ships remained a source of national pride.[56]

Maumoon Presidency

[edit]

As Ibrahim Nasir's second term was coming to an end, he decided not to seek re-election. Thus, in June 1978, the Maldives' legislative body, the Majlis, was called upon to nominate a presidential candidate. Nasir received 45 votes (despite his stated intention not to seek re-election), with the remaining 3 votes cast for Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, a former university lecturer and Maldivian ambassador to the United Nations.[58] Another ballot was called on 16 June. Maumoon received 27 votes, allowing his name to be put forward as the sole candidate.

Five months later, Maumoon was elected the new President of the Maldives with 92.96% of the votes. (He would be later re-elected five times as the sole candidate).[58] The peaceful election was seen as ushering in a period of political stability and economic development due to Maumoon's stated priority to develop the poorer islands.[55] In 1978, Maldives joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.[55] Tourism also increased in importance to the local economy; the country had more than 120,000 visitors in 1985.[55] The local populace appeared to benefit from increased tourism, as well as the corresponding increase in foreign contacts involving various development projects.[55]

There were three attempts to overthrow Maumoon's government during the 1980s: in 1980, 1983, and 1988.[55] Whereas the 1980 and 1983 coup attempts against Maumoon's presidency weren't considered serious, the third coup attempt in November 1988 alarmed the international community,[55] as about 80 armed mercenaries of the PLOTE Tamil militant group[59] landed on Malé aboard used cargo vessels before dawn; they had taken almost 2 days to arrive Male' and failed in controlling the capital city.[citation needed] Their plan was ill-prepared, and by noon, the PLOTE militants and their Maldivian allies fled the country, realizing they had already lost. Soon after the militants had left, the Indian Military arrived on the request of President Gayoom, and their gun ships chased the ships that were being used for escape. 19 people died in the ensuing fight, and several hostages also died when the Indian gun ships fired on the vessel carrying the hostages. Many mercenaries, and also the mastermind of the attempted coup later on, were tried and sentenced to death, later commuted to life in prison. Some were eventually pardoned.[citation needed]

Despite coup attempts, Maumoon served three more presidential terms.[55] In the 1983, 1988, and 1993 elections, Maumoon received more than 95% of the vote.[55] Although the government didn't allow any legal opposition, Maumoon was opposed in the early 1990s by the growth of Islamist radicalization, as well as by some powerful local business leaders.[55]

Maumoon's tenure was marked by several allegations of corruption, autocratic rule, human rights abuses, and corruption.[60][61] Maumoon's opponents and international human rights groups continuously accused him of employing terror tactics against dissidents, such as arbitrary arrests, detention without trial,[62] employing torture, forced confessions, and politically motivated killings.[63]

21st century

[edit]Democratization

[edit]During the later part of Maumoon's rule, independent political movements emerged in Maldives which challenged the then-ruling Dhivehi Rayyithunge Party (Maldivian People's Party, MPP) and demanded democratic reform.

Dissident journalist Mohamed Nasheed founded the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) in 2003 while in exile. He had been imprisoned a total of 16 times under Maumoon's rule. His activism, as well as other events of civil unrest that year, pressured Maumoon into allowing for gradual political reforms.[64]

2003 civil unrest

[edit]Since 2003, following the death in custody of a prisoner, Hassan Evan Naseem, the Maldives experienced several anti-government demonstrations calling for political reforms, more freedoms, and an end to torture and oppression. Naseem had been killed in Maafushi Prison after the most brutal torture by prison staff. An attempt to cover up the death was foiled when the mother of the dead man discovered the marks of torture on his body and made the knowledge public, therefore triggering widespread protests.

A subsequent disturbance at the prison resulted in three deaths when police guards at the prison opened fire on unarmed inmates. Several government buildings were set on fire during the riots. As a result of pressure from reformists, the junior prison guards responsible for Naseem's death were subsequently tried, convicted and sentenced in 2005 in what was believed to be a show trial that avoided the senior officers involved being investigated. The report of an inquiry into the prison shootings was heavily censored by the Government, citing "national security" grounds. Pro-reformists claim this was in order to cover-up the chain of authority and circumstances that led to the killings.

Black Friday protests

[edit]

There were fresh protests in the capital city of Maldives, Malé on 13 August 2004, known as Black Friday, which appeared to have begun as a demand for the release of four political activists from detention.

Beginning on 12 August 2004, up to 5,000 demonstrators got involved. This unplanned and unorganized demonstration was the largest such protest in the country's history. Protesters initially demanding the freeing of the pro-reformists were arrested that afternoon. As the protest continued to grow, people demanded the resignation of president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, who had been in power since 1978.

What started as a peaceful demonstration ended after 22 hours, marking the country's darkest day in recent history. Several people were severely injured as personnel from the Maldivian National Security Service (NSS)—later known as the Maldivian National Defence Force—used riot batons and teargas on unarmed civilians. After two police officers were reportedly stabbed, allegedly by government agents provocateur, President Maumoon declared a state of emergency and suppressed the demonstration, suspending all human rights guaranteed under the Constitution and thus banning demonstrations and the expression of views critical of the government. At least 250 pro-reform protesters were arrested. As part of the state of emergency, and to prevent independent reporting of events, the government shut off internet access and some mobile telephony services to Maldives on 13–14 August.

As a result of these activities, political parties were eventually allowed in June 2005. The main parties registered in Maldives are: the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), the Dhivehi Raiyyithunge Party (DRP), the Islamic Democratic Party (IDP), and the Adhaalath Party (AP). The first party to register was the MDP, headed by popular opposition figures such as Nasheed (Anni) and Mohamed Latheef (Gogo). The next was the Dhivehi Raiyyithunge Party (DRP), headed by Maumoon.

2005 protests

[edit]

New civil unrest broke out in Malé on Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll, as well as Addu Atoll, on 12 August 2005, which led to events that supported the democratic reform of the country. This unrest was provoked by Nasheed's arrest and the subsequent demolition of the Dhunfini tent used by the members of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) for their gatherings.

Supporters of MDP were quick to demonstrate. They started calling for the resignation of Maumoon soon after Nasheed's arrest. The tent's demolition complicated the situation further provoking the unrest. Several arrests were made on the first night. The unrest grew violent on the third night, on 14 August 2005, due to the methods used in the attempts by the authority to stop the demonstration. The unrest lasted from 12–14 August 2005, and by 15 August 2005, the uprising was controlled with the presence of heavy security around Malé. Almost a fourth of the city had to be cordoned off during the unrest.

Tsunami impact

[edit]

On 26 December 2004, following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, the Maldives were devastated by a tsunami. Only nine islands were reported to have escaped any flooding,[65][66] while 57 islands faced serious damage to critical infrastructure. 14 islands had to be totally evacuated, and six islands were destroyed. A further 21 resort islands were forced to close because of serious damage. The total damage was estimated at more than $400 million USD, or around 62% of the country's GDP.[67][68] 102 Maldivians and 6 foreigners reportedly died in the tsunami.[69]

The destructive impact of the waves on the low-lying islands was mitigated by the fact there was no continental shelf or land mass upon which the waves could gain height. The tallest waves were reported to be 14 feet (4.3 m) high.[70]

Nasheed presidency

[edit]A new Constitution was ratified in August 2008, paving the way for the Maldives' first multi-party presidential election two months later.[71][72][73] Standing as the DRP candidate, Maumoon lost in the election's second round; he received 45.75% of the vote against 54.25% for his opponents. The MDP's candidate, Nasheed, accordingly succeeded Maumoon as president on 11 November 2008, with Gaumee Itthihaad's candidate Mohammed Waheed Hassan in the new post of Vice President.

One year later, the 2009 parliamentary election saw the Maldivian Democratic Party, headed by Nasheed, receive the most votes with 30.81%, thus gaining 26 seats. However, Maumoon's MPP, with 24.62% of the vote, received the most seats with 28.

Nasheed's government faced many challenges including the huge debt left by the previous government, the economic downturn following the 2004 tsunami, overspending (by means of overprinting of local currency rufiyaa) during his regime, as well as national issues pertaining to unemployment, corruption, and increasing drug use.[74][unreliable source?] Additionally, taxation on goods was imposed for the first time in the country, and import duties were reduced in many goods and services. Social welfare benefits were given to those above 65 years of age, single parents, and those with special needs.

On 10 November 2008, Nasheed announced an intent to create a sovereign wealth fund with money earned from tourism that could be used to purchase land elsewhere for the Maldives people to relocate in the event that rising sea levels, due to climate change, inundated the country. The government reportedly considered locations in Sri Lanka and India due to cultural and climate similarities, as well as faraway locations like Australia.[69] An October 2009 cabinet meeting was held underwater (ministers wore scuba gear and communicated with hand signals) to publicize the threat of global warming on the low-lying islands of the Maldives.[75]

Political crisis

[edit]A series of peaceful protests broke out in the Maldives on 1 May 2011. They eventually escalated into the resignation of Nasheed amid disputed circumstances in February 2012.[76][77][78][79][80]

The primary cause for the protests had been rising commodity prices and a poor economic situation in the country.[81] Demonstrators protested what they considered the government's mismanagement of the economy, thus calling for Nasheed's ouster. The main political opposition party in the country, the MPP, led by Maumoon, accused President Nasheed of "talking about democracy but not putting it into practice."

Waheed presidency

[edit]

Nasheed resigned on 7 February 2012 following weeks of protests after he ordered the military to arrest Abdulla Mohamed, the Chief Justice of the Criminal Court, on 16 January. The Chief Justice was released from detention after Nasheed resigned from his post.

The Maldives police had joined protesters after refusing to use force on them and took over a state-owned television station, after which they[which?] forcibly switched the broadcast to Maumoon's call for people to come out to protest. The Maldives Army then clashed with police and other protesters who were with the police. All this time, none of the protesters tried to invade any security facility, including headquarters of MNDF.

Shortly after, Vice President Mohamed Waheed Hassan was sworn as the new president of Maldives. Nasheed's supporters clashed with security personnel during a rally on 12 July 2012; they sought the ouster of President Waheed.[82] Nasheed then stated the following day that he was forced out of office at gunpoint, though Waheed supporters maintained that the transfer of power was voluntary and constitutional.[83][84]

A later British Commonwealth meeting concluded that it could not "determine conclusively the constitutionality of the resignation of President Nasheed" but called for an international investigation.[85] The Maldives' Commission of National Inquiry, appointed to investigate the matter, found that there was no evidence to support Nasheed's version of events.[86] Many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, were subsequently quick to abandon Nasheed, instead endorsing his successor. (The United States backtracked in late 2012 in response to widespread criticism.)[64] On 23 February 2012, the Commonwealth suspended the Maldives from its democracy and human rights watchdog while the ousting was being investigated; it also backed Nasheed's call for elections before the end of 2012.[87]

On 8 October 2012, Nasheed was arrested after failing to appear in court to face charges that he had ordered the illegal arrest of a judge while in office. However, his supporters have claimed that this detention was politically motivated in order to prevent him from campaigning for the 2013 presidential elections.[88]

Later, in March 2013, Nasheed was convicted under the country's terrorism laws for ordering the arrest of an allegedly corrupt judge in 2012 and jailed for 13 years. Maldives' international partners—including the EU, US, UK and the United Nations—have said that Nasheed's rushed trial was seriously flawed following a UN panel ruling in the former president's favor. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has called for his immediate release. Nasheed also appealed to the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.[89]

Yameen presidency

[edit]

At the time Nasheed was jailed, Waheed announced that a presidential election would be held in 2013.[90]The elections in late 2013 ended up being highly contested. Nasheed won the most votes in the first round, but contrary to the assessment of international election observers, the Supreme Court cited irregularities and annulled it. In the end, the opposition combined to gain a majority. Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom, half-brother of Maumoon, assumed the presidency.[64]

Yameen implemented a foreign policy shift toward increased engagement with China, thus establishing diplomatic relations between the two countries. Additionally, Yameen employed Islam as a tool of identity politics, framing religious mobilization as the solution to perceived Western attempts to undermine Maldivian national sovereignty. Yameen's policy of connecting Islam with anti-Western rhetoric represented a new paradigmatic development for the country.[64]

On 11 May 2013, Yameen's first Vice President, Mohamed Jameel Ahmed, was removed from office via a no confidence motion by parliament after Yameen's party accused him of trying to overthrow him.[91][92]

On 28 September 2015, there was an assassination attempt on Yameen while he was returning from Saudi Arabia after making the hajj pilgrimage. As his speedboat was docking at Malé, there was an explosion on board. Amid screams, the right door of the boat fell on the jetty, and there grew heavy smoke. Three people were injured, including his wife, but Yameen managed to escape unharmed.[93] In a probe of the incident, Vice President Ahmed Adeeb Abdul Ghafoor was arrested, on 24 October 2015, at the airport upon his return from a conference in China. 17 of Adeeb's supporters were also arrested for "public order offences." The government subsequently began instituting a broader crackdown against political dissent.

On 4 November 2015, Yameen declared a 30-day state of emergency ahead of a planned anti-government rally.[94] The next day, the People's Majlis decided to rush the process for the removal of Adeeb by a no confidence vote that had been submitted by PPM-majority parliament. As a result, the Majlis passed the no confidence vote with a majority of 61 members favoring it, thus removing Adeeb from the post of Vice President in the process.[95] On 10 November 2015, President Yameen revoked the state of emergency, citing that no imminent threats remained in the country.[96]

In 2016, an investigation led by Al Jazeera exposed the Maldives Marketing and Public Relations Corporation scandal in which over $79,000,000 USD was embezzled.[97][98] In the same year, the Maldives left the Commonwealth due to alleged human rights abuses and corruption.[99]

Growth of Islamic radicalism

[edit]In the late 1990s, Wahhabism had challenged more traditional moderate practices; after the 2004 tsunami, Saudi-funded preachers gained influence. Within a short period of a decade, fundamentalist practices began dominating the culture.[100][101]

Since then, many young people in the Maldives have been radicalized and have enlisted in significant numbers to fight for Islamic State militants in the Middle East.[102] In 2015, The Guardian estimated that 50–100 fighters from the Maldives have joined ISIS and al-Qaeda.[101] The Financial Times put the number at 200.[103] Most radicals are young men who suffer from lethargy, unemployment, drug abuse, and the need to prove their masculinity.[101] Radicalization often happens in jail where the "only thing to read is the Qur'an or religious literature. There are also lots of older militants and young guys look up to them."[101]

Solih presidency

[edit]

Ibrahim Mohamed Solih was selected as the new presidential candidate[104] for the coalition of opposition parties in the 2018 election after Nasheed changed his mind about running.[105] In the 2018 elections, Solih won the most votes and was sworn in as the new president on 17 November 2018 after Yameen's five-year term expired. Solih was the seventh president of the Maldives and the country's third democratically elected president. He promised to fight against widespread corruption and investigate the human rights abuses of the previous regime.[citation needed]

Solih also ushered in a change in foreign relations. Yameen had been politically very close to China with some "anti-India" attitude, but Solih reaffirmed the Maldives' previous India-First Policy, after which the Maldives and India strengthened their close relationship.[106][107][108]

On 19 November 2018, Solih announced that the Maldives was set to return to the Commonwealth of Nations, a decision recommended by his Cabinet, considering that the Maldives was a republic in the Commonwealth of Nations from 1982–2016.[109] On 1 February 2020, Maldives officially re-joined the Commonwealth.[110]

In the 2019 parliamentary election, the MDP won a landslide victory. It took 65 of 87 seats of the parliament.[111] This was the first time in Maldivian history that a single party was able to get such a high number of seats in the parliament.[112] Additionally, Yameen was sentenced to five years in prison in November for money laundering. The High Court upheld the jail sentence in January 2021.[113] Later, the Supreme Court acquitted Yameen from the charges on 30 November 2021 due to the lack of substantial evidence.[114]

Muizzu presidency

[edit]

On 17 July 2020, Yameen was selected as the PPM's presidential candidate for the election. However, the Supreme Court rejected Yameen's candidacy because of his sentence.[115][116] As a result, Mohamed Muizzu was elected as a backup candidate for the Progressive Congress Coalition (Progressive Party of Maldives and People's National Congress, PNC) on 3 August 2023.[117]

On 30 September 2023, Muizzu won the second-round runoff of the Maldives presidential election, beating Solih with 54% of the vote.[118] On 17 November 2023, Muizzu was sworn in as the eighth President of the Republic of Maldives.[119] Mohamed Muizzu has been widely seen as pro-China, thus souring the country's relations with India.[120]

In the 2024 parliamentary election, Muizzu's PNC party won a landslide in the parliament.[121][122] It won 70 out of the 93 seats in parliament, making it the second time that a single party was able to get a high number of seats in Maldivian history.[123] As a result, the party earned a super-majority—enough seats to make constitutional changes.[124] In the same year, the High Court overturned Yameen's conviction and ordered a new trial.[125]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ryavec 1995, p. 257.

- ^ "Maldives". Commonwealth of Nations. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "British Indian Ocean Territory". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

The British Indian Ocean Territory has been under continuous British sovereignty since 1814. BIOT is close to the very center of the Indian Ocean, mid-way between Tanzania and Indonesia. Its nearest neighbours are the Maldives and Sri Lanka.

- ^ "History". Embassy of the Maldives, Brussels. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Colliers Encyclopedia (1989) VO115 P276 McMillan Educational Company

- ^ a b c d e Mohamed, Naseema (2005). "Note on the Early History of the Maldives". Persée. 70: 7–14. doi:10.3406/arch.2005.3970. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Pijpe, J.; Voogt, A.; Oven, M.; Henneman, P.; Gaag, K. J.; Kayser, M.; Knijff, P. (2013). "Indian Ocean Crossroads: Human Genetic Origin and Population Structure in the Maldives". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 151 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22256. PMC 3652038. PMID 23526367.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Maldive Antiquity". antu.s5.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2004.

- ^ Ellis, Royston (1 January 2008). Maldives. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841622668. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b Maloney, Clarence. "Maldives People". International Institute for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 29 January 2002. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ Kalpana Ram, Mukkuvar Women. Macquarie University. 1993

- ^ Philostorgius, Church History, tr. Amidon, pp.41–44; Philostorgius' history survives in fragments, and he wrote some 75 years later than these events.

- ^ Kulikov, L.I. (2014). "Traces of castes and other social strata in the Maldives: a case study of social stratification in a diachronic perspective (ethnographic, historic, and linguistic evidence)". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 139 (2): 199–213 [205]. hdl:1887/32215.

- ^ Clarence Maloney. People of the Maldive Islands. Orient Longman

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "TRADE AND BUDDHIST KINGDOMS IN THE ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL MALDIVES | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ Mikkelsen, Egil (2000). "Archaeological Excavations of a Monastery at Kaashidhoo. Cowrie shells and their Buddhist context in the Maldives" (PDF). National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Research. University of Oslo, Norway. ISBN 99915-1-013-3. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ a b "The Lion Throne Coronation Proclamation of King Siri Kula Sudha Ira Siyaaka Saathura Audha Keerithi Katthiri Bovana". Maldives Royal Family. 21 July 1938. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Legend of Koimala Kalou". Maldives Royal Family. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ This was in order to care for a shipwrecked British steamer's load. Bell moreover had the chance to spend two or three in Malé, on the same occasion. See: Bethia Nancy Bell, Heather M. Bell: H.C.P. Bell: Archaeologist of Ceylon and the Maldives, p.16. Archived 3 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ryavec 1995, p. 258.

- ^ Ryavec 1995, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354, tr. and ed. H. A. R. Gibb (London: Broadway House, 1929)

- ^ a b Dunn, Ross E. (1986). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520057715. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016.[page needed]

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 235–236, 320. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Honchell, Stephanie (2018), Sufis, Sea Monsters, and Miraculous Circumcisions: Comparative Conversion Narratives and Popular Memories of Islamization, World History Connected, p. 5,

reference to Ibn Battuta's theory that this figure hailed from Morocco, citation 12 of this article mentions that other accounts identify Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari as East African or Persian. As a Maghribi himself, Ibn Battuta likely felt partial to the Moroccan version.

- ^ Columbia University (24 November 2010). Richard Bulliet - History of the World to 1500 CE (Session 22) - Tropical Africa and Asia. YouTube. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Ibn Batuta (1968). Monteil, Vincent (ed.). Voyages d'Ibn Battuta:Textes et documents retrouves (in Arabic). Anthropos. p. 127.

- ^ Kamala Visweswaran (6 May 2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Ishtiaq Ahmed (2002). Ingvar Svanberg; David Westerlund (eds.). Islam Outside the Arab World. Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 9780253022608. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ HCP Bell, The Máldive Islands. Monograph on the History, Archæology, and Epigraphy with W. L. De Silva, Colombo 1940

- ^ Paul, Ludwig (2003). Persian Origins--: Early Judaeo-Persian and the Emergence of New Persian: Collected Papers of the Symposium, Göttingen 1999. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-447-04731-9. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Boomgaard, P. (1 January 2008). Linking Destinies: Trade, Towns and Kin in Asian History. BRILL. ISBN 9789004253995. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gracias, Fatima da Silva (1996). Kaleidoscope of Women in Goa, 1510-1961. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-591-1.

- ^ "އައްސުލްޠާނުލް ޤާޒީ މުޙަންމަދު ތަކުރުފާނުލް އަޢުޘަމް ސިރީ ސަވާދީއްތަ މަހާރަދުން" [As-Sultan Ghaazee Muhammad Thakurufaan Al-Auzam Siri Savaadheetha Mahaaradhun] (PDF). National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "History of Maldives". Lets Go Maldives. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ GihKiyaafa (3 November 2018). "The story of Muhammad Thakurufaanu is a story of bravery and freedom". Facebook. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryavec 1995, p. 259.

- ^ "Working Together to Protect U.S. Organizations Overseas". Overseas Security Advisory Council. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Tan, Kevin; Hoque, Ridwanul (2021). Constitutional Foundings in South Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 978-1509930272.

- ^ Kearney, Jonathan (23 September 2020). "Fascinating History of How WWII Brought to the Maldives". Maldives Traveller. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ a b "President Al Ameer Mohamed Amin". The President's Office. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ a b Hamdhoon, Mohamed (16 October 2020). "އިބްރާހިމް ދީދީ: ބާރުވެރިކަން، އިންގިލާބު އަދި އަރުވާލުން!" [Ibrahim Didi: Power, Revolution and Exile!]. Mihaaru. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Faiza, Aminath (1999). އަމީނުގެ ހަނދާން [Amin's remembrance].[page needed]

- ^ "Killed, exiled or deposed". Maldives Independent. 15 November 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Republic Day: The celebrations of November 11th". Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ryavec 1995, p. 260.

- ^ "Association of RAF Mauripur". Association of RAF Mauripur. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008.

- ^ "Situation in the Maldives (Letter to the Editor)". Maldives Royal Family. 25 May 1959. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Abdullah Afif Didi (Hansard, 5 December 1963)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "The Sun never sets on the British Empire". Gan.philliptsmall.me.uk. 17 May 1971. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Malediven, 15. März 1968 : Staatsform" [Maldives, 15 March 1968: Form of government]. Direct Democracy (in German). 15 March 1968. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Ryavec 1995, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Hyde, Neil (21 November 2012). "Maldives magic uncorked". Daily Express. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Ryavec 1995, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ryavec 1995, p. 261.

- ^ a b Lang, Olivia; Rasheed, Zaheena (22 November 2008). "Former President Nasir Dies". Minivan News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ Clarence Maloney. People of the Maldive Islands

- ^ a b "History". Country Studies. Library of Congress. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Country Data - Maldives". Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies. Archived from the original on 13 July 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- ^ Naseem, Azra (21 October 2010). "MP Moosa Manik files torture complaint against former President Gayoom". Minivan News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Gayoom is fully aware of torture in the Maldives". Maverick Magazine. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Maldives dissident denies crimes". BBC News. 19 May 2005. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Amnesty International Report 2004 – Maldives". Refworld. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Amnesty International. 26 May 2004. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Brechenmacher, Victor; Mendis, Nikhita (22 April 2015). "Autocracy and Back Again: The Ordeal of the Maldives". Brown Political Review. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Maldives – Country Review Report on the Implementation of the Brussels Programme of Action for LDCS" (PDF). United Nations. Ministry of Planning and National Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Maldives Skyscraper – Floating States". eVoLo. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "UNDP: Discussion Paper – Achieving Debt Sustainability and the MDGs in Small Island Developing States: The Case of the Maldives" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Maldives tsunami damage 62 percent of GDP: WB". China Daily. 15 February 2005. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Sinking island nation seeks new home". CNN. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Republic of Maldives – Tsunami: Impact and Recovery" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ Buerk, Roland (7 August 2008). "Maldives adopt new constitution". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Voting extended in Maldives poll". BBC News. 8 October 2008. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Vote count underway after landmark Maldives election". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 8 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ "The Quality of Political Appointees in the Nasheed Administration". Raajje News. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Maldives cabinet makes a splash". BBC News. 17 October 2009. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Maldives crisis: Top 10 facts". NDTV. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Hull, C. Bryson (11 February 2012). "Pressure builds for probe into Maldives' crisis". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Lang, Olivia (17 February 2012). "Q&A: Maldives crisis". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Maldives crisis: Commonwealth urges early elections". BBC News. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Maldives crisis means trouble for India". Zee News. 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, R. K. (3 May 2011). "Blake leaves strong message for Maldivian opposition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "Nasheed supporters, police clash in Maldives". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 13 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Lawson, Alastair (6 April 2012). "Maldives elections will not be in 'foreseeable future'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Maldives president quits after police mutiny, protests". Reuters. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Maldives crisis: Commonwealth urges early elections". BBC News. 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Sen, Ashish Kumar (30 August 2012). "Maldives panel: President was not forced to resign". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Griffiths, Peter (22 February 2012). "Commonwealth suspends Maldives from rights group, seeks elections". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Mallawarachi, Bharatha (8 October 2012). "Mohamed Nasheed, Former Maldives President, Arrested After Failing To Appear in Court". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ Naafiz, Ali (20 October 2015). "Maldives opposition seeks India's help in jailed leader's release". Haveeru Daily. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Francis, Krishan (18 April 2012). "Maldives Election: President Mohammed Waheed Hassan Calls For Early Vote In 2013". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ Rehan, Mohamed (12 February 2018). "Ruling party accuses ex-VP Jameel on 'plot to overthrow govt'". Avas. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Muhsin, Mohamed Fathih Abdul (15 February 2021). "Was removed from office without being allowed a proper defense: Dr Jameel". The Times of Addu. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Iyengar, Rishi (28 September 2015). "Maldives President Abdulla Yameen Escapes Unhurt After Explosion on His Boat". TIME. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Maldives declares 30-day emergency". BBC News. 4 November 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Majlis passes declaration to remove VP from office". People's Majlis. 5 November 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016.

- ^ "Maldives revokes state of emergency amid global outcry and tourism worries". The Guardian. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "US$79m embezzled in Maldives' biggest corruption scandal". Maldives Independent. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Maldives government must ac on new details in corruption scandal". Transparency International. 18 February 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Safi, Michael (13 October 2016). "Maldives quits Commonwealth over alleged rights abuses". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Boland, Mary (16 August 2014). "Tourists blissfully unaware of Islamist tide in Maldives". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d Burke, Jason (26 February 2015). "Paradise jihadis: Maldives sees surge in young Muslims leaving for Syria". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Bosley, Daniel (24 October 2015). "Maldives vice president arrested in probe of explosion targeting president". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Mallet, Victor (4 December 2015). "The Maldives: Islamic Republic, Tropical Autocracy". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Junayd, Mohamed (1 July 2019). "Maldives opposition selects veteran Ibrahim Solih for Sept presidential poll". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Munavvar, Rae (1 July 2018). "MP Ibu declared MDP's Presidential Candidate". The Edition. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Rasheed, Zaheena (17 November 2018). "Ibrahim Mohamed Solih sworn in as new Maldives president". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai (28 September 2018). "Maldives Shock Election: China's Loss and India's Win?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Malsa, Mariyam (8 June 2019). "President Solih reaffirms India-first policy". The Edition. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Maldives to participate in the Commonwealth again". The President's Office. 19 November 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2024.